Long ago and just a few years into my yoga practice, my teacher Donald Moyer gave a brief talk before class that was revelatory for me. A dedicated and revered teacher, Donald generally took a pragmatic approach to his classes. He did not typically share anything personal. But this day was different. He had recently lost his father and was deep into the grieving process. “Backbends are the recommended practice for dealing with depression,” he told us. “But I am not up to doing backbends these days. I don’t have the energy for that. All I can manage right now is to sit on the floor and practice forward bends.”

Like many westerners, I had come to yoga for the exercise and physical benefits. I had immediately fallen in love with how great I felt after class, and then over time, with how it helped me heal the chronic pain that knee injuries had left me with. But while I was aware that practicing elevated my mood and overall well-being, it still hadn’t occurred to me that I could intentionally focus my practice depending on my emotional state—that I could use it prescriptively for emotional issues, not just physical ones. His remarks were hugely influential on my developing practice and also later, as I became interested in positive psychology and the mind/body connection to happiness.

I studied with Donald for many years and then, after he invited me to join the staff of the teacher training program he directed at the Berkeley Yoga Room, we gradually became friends as well, going out to lunch from time to time. Because he didn’t drive, we would usually go someplace in downtown Berkeley, within walking distance of his house. One day I suggested that instead I could drive us to a favorite of mine, Oliveto’s Café in Oakland, a terrific Italian restaurant. He loved it and it became our regular spot. “It’s Friday,” he would say to me as soon as we sat down, his eyes twinkling. “I’m going to have a glass of wine!” And he would order a chardonnay.

Although he never explicitly said so, I always thought that one thing Donald appreciated about me was that while I admired and respected him enormously, I didn’t idolize him as so many of his students did. He was real person to me and I treated him that way. We shared a love of theater and at our lunches, rather than talking about yoga, we would often discuss plays we had seen, books we were reading and what we were watching on television. He surprised me when he mentioned he’d been enjoying watching Sex in the City! He was hugely supportive of my writing and wrote a beautiful recommendation for me when I decided to apply to graduate school.

Decades after the loss of his father, Donald’s own health declined. He had Parkinson’s Disease and had also had several bouts of Lymphoma during his life; the rounds of chemo and medication had taken a toll and left him debilitated. Our occasional lunches continued but it was clear he wasn’t doing well and it was very hard to see this special person who had been a mentor and an inspiration suffering. He talked with some anguish about his physical decline and also his questioning around how he’d spent his life, a very sad thing to hear from someone who was so beloved by his students and had supported and inspired so many other yoga teachers. On a brighter note, he had decided to reread all of Shakespeare’s plays as a sort of bucket list project and enjoyed telling me about that. He also continued to enjoy a glass or two of chardonnay at our favorite lunch spot.

Then one day I reached out to schedule lunch and he sent an email back saying that he was absorbed with managing his health and wasn’t up to meeting. It was a very sobering note to get, I had to catch my breath after reading it. He said that he would still love to hear all about what I was doing and suggested I send an email catching him up on all that was going on in my life. It took me awhile to sit down and write that email—too long— and by the time I did, I learned that he had moved to assisted living. When I went to visit him there, it was shocking to see how much he had declined, and very painful to witness the loss of mobility and independence in someone who had devoted his life to yoga. Someone I loved. He told me that his eyes had been affected by the Parkinson’s and said how sorely he missed reading. I asked him if he would like me to read to him. He was delighted by the offer and suggested King Lear. “Are you sure?” I asked him. “We could choose something lighter. What about Twelfth Night?”

He insisted on King Lear. “I am very interested in Shakespeare’s insights on the decline and suffering of old age,” he told me. So… we read King Lear together. Although we didn’t get very far, he was very engaged in both listening and then discussing what we had read.

I recall another of my early yoga teachers saying that he couldn’t believe how great he felt after taking his first yoga class, and that his immediate thought was “why shouldn’t I feel great all the time?!” And I’ll admit I have often felt similarly about practicing yoga. The well-being boost, both immediate and cumulative, has been very motivating, and made my mat very inviting. It has kept me practicing for decades.

But feeling great all the time isn’t truly available. Human life inevitably holds change, difficulties, sorrow and pain as well as joy, awe and contentment. Yoga can be a source of comfort and give us tools for coping as we navigate all of that, but it is not an escape from the reality of life. Nor should it be.

When Donald went into hospice care, he stopped having visitors. I saw him one more time by accident, though, when I went by his care facility on his birthday with a card and a note of appreciation for what he had meant to me. I had intended just to drop it off for him, but the staff at the front desk ushered me back to see him. “Are you sure,” I asked. “I think he isn’t seeing people these days. Do you want to check with him first?” “Oh, no, he’ll be so happy to see you,” they assured me.

He looked at me like a deer in the headlights when I appeared in his doorway, though, and I thought the receptionist had probably been mistaken. But it was too late. Luckily two aids were with him, and they helped him sit up in his bed; he had lost the ability to do that by himself. I told him I had come because I was thinking of him on his birthday and gave him my card and letter. I apologized for intruding, and he looked at me with his customary twinkle, then said “You’re not the first one.” We looked at each other fondly for a moment and then I gave him a quick hug and said goodbye for the last time, hoping someone would read him the letter I’d enclosed later.

I realized that Donald hadn’t wanted people to see what he was enduring and regretted the misstep of the visit. At the same time, though, we had a lovely moment of connection and I was glad that I got to say a final goodbye. I hadn’t anticipated my previous visit would be the last one and, when I learned that he had stopped seeing people, had been bereft at the thought that I would never see him again. But the reality is that we can’t and often don’t know when the last time we’ll see a loved one will be. When I mentioned my regret to a friend who had lost both her parents and also knew Donald, she reassured me. “It’s always messy,” she said. “And it’s different for everyone. There’s just no way to know what’s going to be right for someone.”

Donald died a few months later. It hit me hard when I got the news he had passed, but it was also a relief. He had suffered so terribly in his last year, and I knew it was a blessing that his suffering was over. I was also reminded of another way those remarks about the death of his father had influenced me. In the weeks after that long ago class I continued to think deeply about what he had said and had realized that depression and grief are not the same, and that the prescriptions should also be different. Chronic and clinical depression are medical conditions that require treatment, whether it comes from holistic measures such as yoga or from the pharmacy (or some combination). There is no antidote to grief, though, except for time. Grief is an important part of life that we all must experience and that deserves to be honored.

Donald’s death was a deep loss, yet I understood that it was also just another step in a process of loss that had been occurring over the previous few years. I also knew that I would miss him forever. I learned from Donald, and then from my continued exploration in my own yoga practice, that yoga offers a rich variety of tools for helping us navigate our emotions and the challenges of life. I was so blessed to have Donald in my life, and still think of him daily when I’m on my yoga mat, with gratitude.

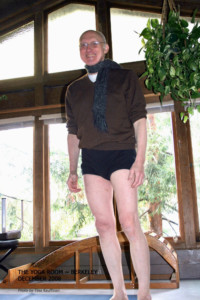

Photo by Tina Kauffman

In Memorium

Donald Moyer

July 9, 1939 – November 7, 2019